The Gesangleiter in Joseph Riepel’s Baßschlüssel (1786) – First Part

Stefan Eckert

Joseph Riepel’s Anfangsgründe zur musikalischen Setzkunst (Fundamentals of Musical Composition) is an important source for our understanding of eighteenth-century compositional theory and pedagogy. One of the most noticeable aspects of the Anfangsgründe is the fact that the treatise is written in dialogue form. Only the chapter published posthumously in 1786, the Baßschlüssel (Bass clef), which focuses on how to write a bass against an existing melody, does not, except for the last four pages, follow the dialogue format. Because of this, the Baßschlüssel seems to present a different theoretical approach to composition. Most noteworthy is the absence of other theoretical positions that result from the typical back and forth between teacher and student. While the original manuscript upon which the edited version is based does not seem to have survived, a manuscript copy held in the British Library (GB-Lbl Add. 31034) contains at least twelve pages in dialogue form that are related to the Baßschlüssel, but that are not part of the published chapter. These twelve pages relate to Riepel’s Gesangleiter, his instruction on how to harmonize ascending and descending scale steps in the upper voice, which follows his discussion of the Baßleiter, the harmonization of scale steps in the lowest voice, or bass. The following essay, provides an overview of the Gesangleiter in Riepel’s Baßschlüssel, followed by a discussion of the manuscript pages as compared to the published version and a transcription of the manuscript pages.

Joseph Riepel’s Anfangsgründe zur musikalischen Setzkunst ist eine der zentralen Quellen für unser Verständnis der Kompositionstheorie und pädgogik im achtzehnten Jahrhundert. Ein auffallendes Merkmal der Anfangsgründe ist das das Traktat in der Form eines Dialoges verfasst ist. Nur der nach Riepels Tod veröffentlichete Baßschlüssel, das Kapitel das darauf fokusiert wie man einen Baß zu einer bestehenden Melodie setzt, ist, abgesehen von den letzten vier Seiten, nicht in Dialogformat. Deshalb scheint der Baßschlüssel einen ganz anderen theoretischen Ansatz zur Komposition darzulegen. Am auffallensten ist die Abwesenheit von unterschiedlichen theoretischen Positionen die ein Resultat des typischen hin under her zwischen Lehrer und Schüler sind. Obwohl das orginale Manusript auf dem die herausgegebene Version basiert nicht überliefert ist, eine Kopie der British Library (GB-Lbl Add. 31034) enthält wenigsten zwölf Seiten in Dialogform die mit dem Baßschlüssel zusammenhängen aber nicht Teil des publizierten Kapitels sind. Diese zwölf Seiten beziehen sich auf Riepels Gesangleiter, seine Anleitung wie man auf- und absteigende Tonstufen in der Oberstimme harmonisiert, die auf die Baßleiter, der Anleitung wie man Tonstufen in der Unterstimme, dem Baß, harmonisiert, folgt. Der folgende Beitrag liefert eine Überblick über die Gesangleiter in Riepels Baßschlüssel gefolgt von einer Besprechung der Manuskriptseiten im Vergleich mit dem publizierten Kapitel und einer Abschrift der Manuskriptseiten.

Joseph Riepel’s Anfangsgründe zur musikalischen Setzkunst (Fundamentals of Musical Composition) was among the first treatises to discuss composition on the basis of combining measures and to address musical form on the phrase level.[1] Recognized by contemporaries for offering hands-on instructions and practical suggestions for budding composers, Riepel’s treatise continues to be an important source for our understanding of eighteenth-century compositional theory and pedagogy.[2] The Anfangsgründe consists of ten chapters, five of which were published by Riepel during his lifetime between 1752 and 1768. Two chapters were edited and published posthumously in 1786 in one volume by Johann Caspar Schubarth (who was one of Riepel’s former students); another three chapters have survived in manuscript form.[3] One of the most noticeable aspects of the Anfangsgründe is the fact that the treatise is written in dialogue form. According to Riepel, the different chapters resemble actual lessons in composition, unfolding as lively discussions between a teacher, the Præceptor, and his student, the Discantista. Only the chapter published posthumously in 1786, the Baßschlüssel (Bass clef) does not, except for the last four pages, follow the dialogue format. Because of this, the Baßschlüssel seems to present a different theoretical approach to composition. This change in structure is most profound when noting the absence of other theoretical positions that result from the typical back and forth between teacher and student. Because Riepel usually does not present compositional issues as codified theory, but instead uses the dialogue to convey the multifarious aspects of mid-eighteenth-century musical practice, this difference is highly significant.[4]

While the original manuscript upon which the edited version is based does not seem to have survived, a manuscript copy held in the British Library (GB-Lbl Add. 31034) contains at least twelve pages in dialogue form that are related to the Baßschlüssel, but that are not part of the published chapter.[5] Since no copy of the original manuscript seems to exist, it is impossible to know which aspects of the treatise were changed by the editor, Johann Kaspar Schubarth, and which can be traced back to Riepel. In his listing of Riepel’s works, Thomas Emmerig stated that “[a]fter the [manuscript] copy of the Baßschlüssel in GB-Lbl. [the British Library] follow 22 pages (fol. 71a–92b), ‘which do not appear in the published edition’ (Hughes-Hughes III, 326). These pages are without any doubt fragments of earlier manuscript versions, among others of the Baßschlüssel–in its original dialogue form!–and of the Harmonisches Sylbenmaß III; some parts could not be identified. Whether these constitute autograph pages or copies cannot be ascertained, because proven autographs from Riepel’s earlier years for comparison are missing. Literature: Mettenleiter, 52 – Twittenhoff, 38 ƒ. and 107 ƒƒ.”[6] Emmerig refined his assessment of the forty-four single pages in the appendix to the complete edition, stating that 12 pages related to the Baßschlüssel still remain unidentified in their content.[7]

I have transcribed these twelve pages and identified that their content relates to Riepel’s Gesangleiter, his instruction on how to harmonize ascending and descending scale steps in the upper voice, which follows his discussion of the Baßleiter, the harmonization of scale steps in the lowest voice, or bass. While the manuscript pages approach the Gesangleiter from different perspectives, several passages seem fragmented and slightly cryptic, almost as if they were taken from another context or constituted only a preliminary stage of the material. However, the employment of different perspectives compares well with the overall approach in the rest of the Anfangsgründe and complements the opening sections of the Baßschlüseel which seems to offer a somewhat categorical approach to the material. It is also noteworthy that the first five pages of the Baßschlüssel, which contain the Baßleiter, restate material already presented in the previous chapter on Counterpoint, a situation that is unique within the Anfangsgründe.[8] In the following essay, I provide an overview of the Gesangleiter in Riepel’s Baßschlüssel, followed by a discussion of the manuscript pages as compared to the published version. My transcription of the manuscript pages follows in a separate article. While the content of the manuscript pages, due to their limited size and the topics addressed, do not reveal any extraordinary new insight into Riepel’s ideas, it is interesting how there is a distinct reorganization of the material. In addition, despite its scholarly neglect, Riepel’s Gesangleiter does offer interesting insights into his conception of the interaction between melody, harmony, and counterpoint and thus deserves our attention.

* * *

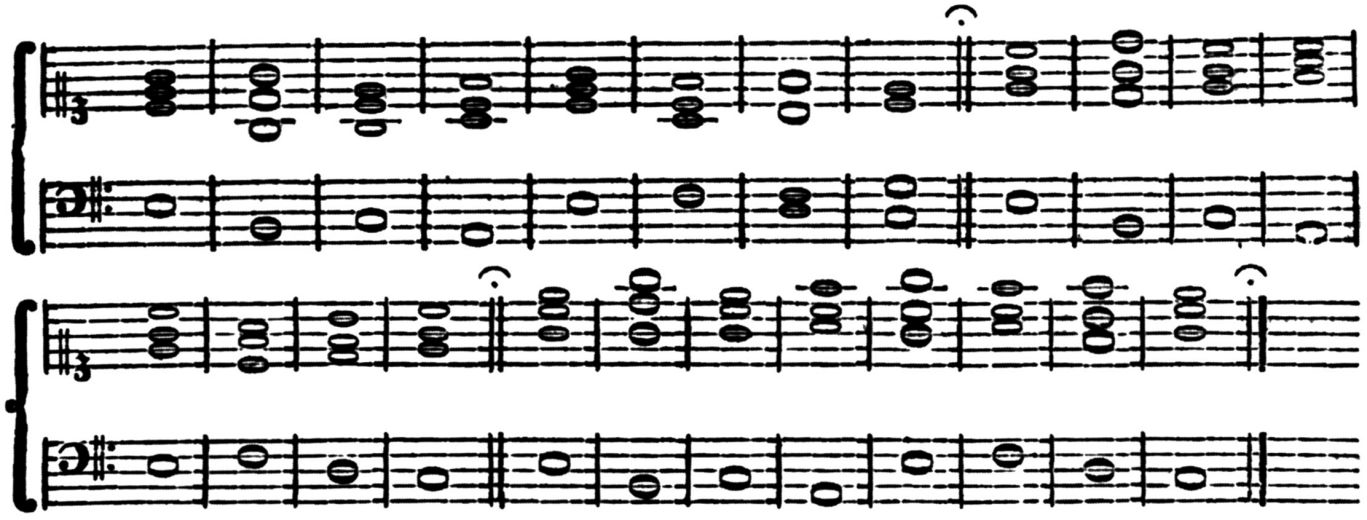

The Baßschlüssel, das ist, Anleitung für Anfänger und Liebhaber der Setzkunst, die schöne Gedanken haben und zu Papier bringen, aber nur klagen, daß sie keinen Baß recht dazu zu setzen wissen (Bass clef, that is, instruction for beginners and music lovers, who have beautiful ideas and can notate them, but who complain that they do not know how to set a proper bass against them), is intended to teach students how to write a bass against an existing melody and consists largely of two parts. Figure 1 provides an overview of the topics and demonstrates that the Baßleiter and the Gesangleiter make up the largest sections of the treatise. The Baßleiter, which is also known as the Rule of the Octave, builds the foundation for the Gesangleiter, which constitutes Riepel’s idiosyncratic appropriation of the octave rule to the highest voice.[9]

Figure 1: Contents of Riepel’s Baßschlüssel (84 pages)

While the Baßleiter and the Gesangleiter create an overarching structure for the Baßschlüssel, there exist significant portions, especially pages 33–63, that do not explicitly relate to either of the two topics. Also, while the Gesangleiter in major is treated in great detail, the minor and chromatic versions are only mentioned briefly, without additional examples for their applications. I begin with a summary of Riepel’s Baßleiter and provide a more detailed discussion of Riepel’s ascending and descending Gesangleiter in major, which consists of twenty-six rules, and end with an overview of the extension of the Gesangleiter in minor and a brief account of the final, rather loosely connected rules around Gesangleiter and Baßleiter, including some chromatic issues, with which Riepel ends the Baßschlüssel.

Riepel’s Baßleiter

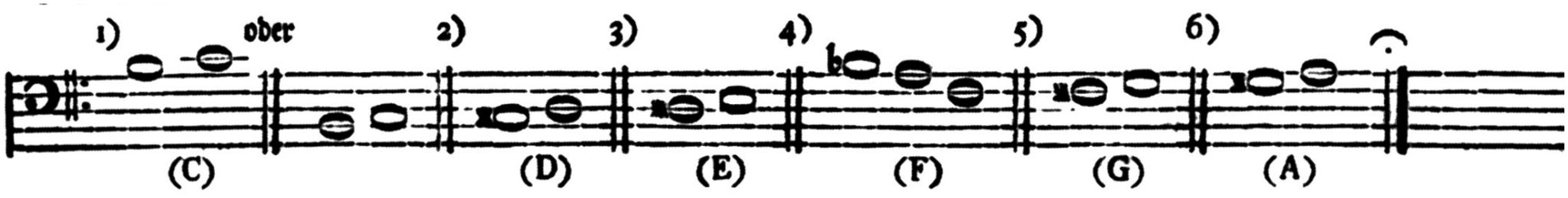

Riepel begins the Baßschlüssel with a discussion of the common (allgemeine) Baßleiter, that is, the rules on how to harmonize the different pitches within a scale, assuming mostly stepwise motion. For the ascending scale, Riepel sets root position chords above scale degrees ➀, ➃, and ➄, and first inversion triads on scale degrees ➁, ➂, ➅, and ➆.[10] However, he points out that composers often harmonize scale degrees ➃ and ➆ with a 6/5 and scale degree ➁ with a 6/4/3; the latter he shows in both ascending and descending motion: ➀–➁–➂ and ➂–➁–➀ (Figure 2):

Figure 2: Ascending scale with major third [Aufsteigende Leiter mit der großen Terz] (including variants)

For the descending scale, he keeps root position chords on scale degrees ➀ and ➄, but harmonizes ➃ with a 4/2. In addition, he harmonizes scale degree ➅ with ♯6, a major sixth (Figure 3):

Figure 3: Descending scale with major third [Absteigende Leiter mit der großen Terz]

In addition, he highlights further context-specific harmonization of scale degrees ➅, ➃, and ➁ (Figure 4). While ➅–➄ be harmonized with a major sixth (♯6), if scale degree ➄ does not follow scale degree ➅, then it should be harmonized with just a minor sixth (6). In addition, if scale degree ➅ is approached by step from either direction without a stepwise continuation, it should be harmonized with a 5/3. Scale degree ➃ should be harmonized with a 4/2 when moving ➄–➃–➂; however, if scale degree ➃ moves to ➂ without the context of a Dominant chord, it should be harmonized with a 5/3. Similarly, while scale degree ➁ is usually harmonized with a 6 or 6/4/3, if it does not move stepwise within a Tonic chord, that is scale degrees ➀ and ➂, it should be harmonized with a 5/3. I have summarized these context-specific harmonizations of ➅, ➃, and ➁ in Figure 4 below:

Figure 4: Context-Specific Harmonization of ➅, ➃ and ➁

As Example 1 demonstrates, Riepel suggests fixed harmonizations for scale degrees ➀, ➂, ➄, and ➆ and flexible, that is, context-specific harmonizations of scale degrees ➁, ➃, and ➅:

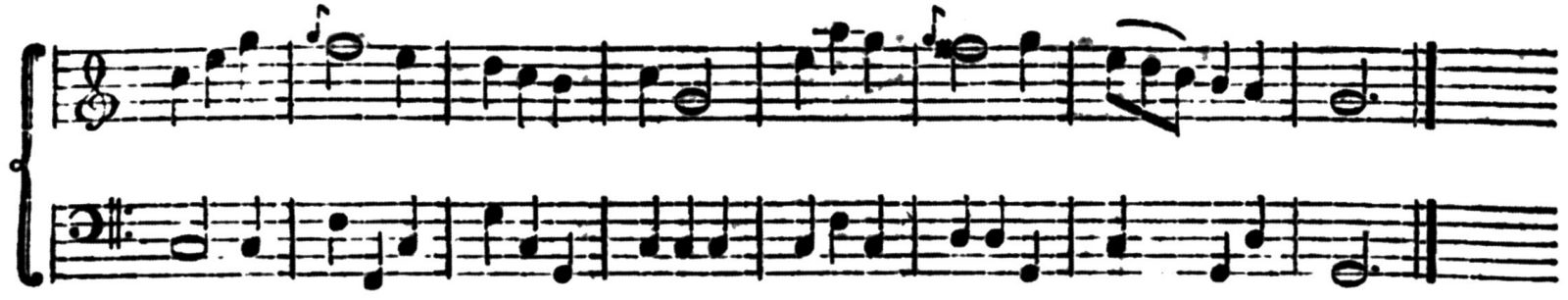

Example 1: Baßleiter, p. 3 (measure numbers added)

The fixed harmonizations result in root position chords for scale degrees ➀ and ➄ and first inversion triads on scale degrees ➂ and ➆; with the possibility of the latter taking a 6/5, that is, a chordal seventh. Scale degree ➁ may be harmonized with a root position chord if ➁ does not move to tonic harmony (that is, to either scale degrees ➀ or ➂) as seen in mm. 12 and 19; scale degrees ➃ and ➅ may be harmonized with root position chords, if ➃ and ➅ do not move to a dominant chord (that is, ➄ or ➆) as it happens for ➃ in mm. 11 and 22 and for ➅ in m. 17. In addition, ➅ takes a major sixth (♯6) moving to ➄ as in mm. 6–7, but a minor sixth (6) when it does not moves to ➄ as in m. 10.

For the ascending minor scale (Figure 5), all changes are due to the mode change, otherwise the same rules as in the ascending major scale apply. In contrast, the descending minor scale (Figure 6) with its flattened scale degrees ♭➅ and ♭➆ usually does not include the major sixth (♯6) in its stepwise descend to ➄. With the exception of the major sixth (♯6) and the necessary alteration due to the lowered third and sixth scale degrees (♭➂ and ♭➅), the other context-specific harmonization of scale degrees ➁, ➃, and ➅ as outlined in Figure 4 above apply also in minor.

Figure 5: Ascending scale with minor third

Figure 6: Descending scale with minor third

Riepel follows this overview of the octave rules in major and minor with a reminder that a minor second below a scale step indicates scale degree ➆, the leading tone, which he calls Septimensprung (leap of a seventh) of a new key. Listing all the closely related keys, which he calls Mitteltonarten in Example 2, it is noteworthy that F is identified not by scale degree ➆, E, but by Bb–A–F (➃–➂–➀).

Example 2: Mitteltonarten (Closely Related Keys), p. 4

Finally, Riepel ends his presentation of the octave rule with two unfigured basses in both major and minor as examples for applying the octave rule to a bass that moves to all closely related keys. The bass lines appear first without figures but with annotations identifying the different keys followed by a figured version that provides the answer key on how the bass lines should be harmonized.

What is unique about the presentation of the octave rule in the opening five pages of the Baßschlüssel, is that this constitutes the second complete presentation of the octave rule within the Anfangsgründe. Indeed, halfway through Chapter Six “On Counterpoint,” at a moment when Riepel rewrites counterpoint examples by J.J. Fux from a harmonic perspective, the teacher already introduces the octave rule to the student.[11] While the content of the two presentations is essentially the same, that is, the information concerning how specific scale degrees should be harmonized, the differences between the two presentations are significant. Most importantly, the presentation of the octave rule at the beginning of the Baßschlüssel is not in dialogue form and proposes root position chords above scale degrees ➀, ➃, and ➄, as a matter of nature.

Since the fourth F and the fifth G demand by nature a complete chord [The Baßschlüssel defines a complete chord as consisting of a third and fifth, either of which may be omitted in practice[12]], yet their immediate progression easily leads to forbidden fifths or octaves, even the oldest masters have used the six-five chord as a good emergency assistance. Although it sounds somewhat drudging, it is often used for [above] the seventh as well as the fourth [scale degree].[13]

Joel Lester has suggested that such emphasis on scale degrees ➀, ➃, and ➄ demonstrates that Riepel embraces “aspects of Rameauian harmony.”[14] Yet, the introduction to the octave rule in the counterpoint chapter does not contain this reference to nature, and the student-teacher discussion does not sound as categorical as the opening in the Baßschlüssel. Moreover, throughout the Anfangsgründe, Riepel either ignores or comments negatively on Rameau’s mathematically grounded principles of music, which he considers to stand in contrast with his hands-on approach. For example, he compares the ideas contained in one of Rameau’s treatises, Démonstration du Principe de l’Harmonie, to a satire by Ludvig Holberg, stating, “I was just as eager to read [Rameau’s] treatise as I was to know how Nicolaus Klim finally found a fifth monarchy in the center of the earth.”[15]

Riepel’s Gesangleiter

I would first like to note that the ancient bass, which accompanies a melody [Gesang] has been explained by some to be systematical (perhaps only in this century). According to this explanation, the whole octave scale has only three Grundbaßnoten [fundamental-bass notes], the remainder are neighboring or passing tones, which I in appreciation of their good service call at least Mittelbaßnoten [middle-bass notes] (6).[16]

This opening statement, with which the author of the Baßschlüssel begins the presentation of the Gesangleiter seem foreign to Riepel’s ideas. Most importantly the claim that the bass derives from a system, which reduces it to three fundamental bass notes, seems reminiscent of Rameau’s ideas. However, as mentioned in the context of Riepel’s discussion of the octave rule, there does not really exist enough evidence to substantiate a specific relationship. The Gesangleiter with its various and usual bass notes [mit ihren verschiedenen und üblichen Baßnoten] directly and indirectly takes up the majority of the Baßschlüssel. Since the Baßschlüssel is not in dialogue form, there exists no back and forth between the teacher and student, no questions are raised, and no contradictions appear. On the other hand, the single authorial voice allows for an uninterrupted presentation of the topics at hand. Even though we are unable to prove or disprove Riepel’s authorship of the printed version of the Baßschlüssel, I continue to identify him as the author in the following discussion.

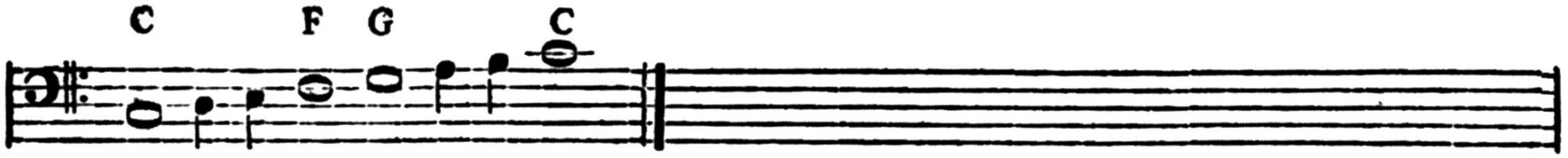

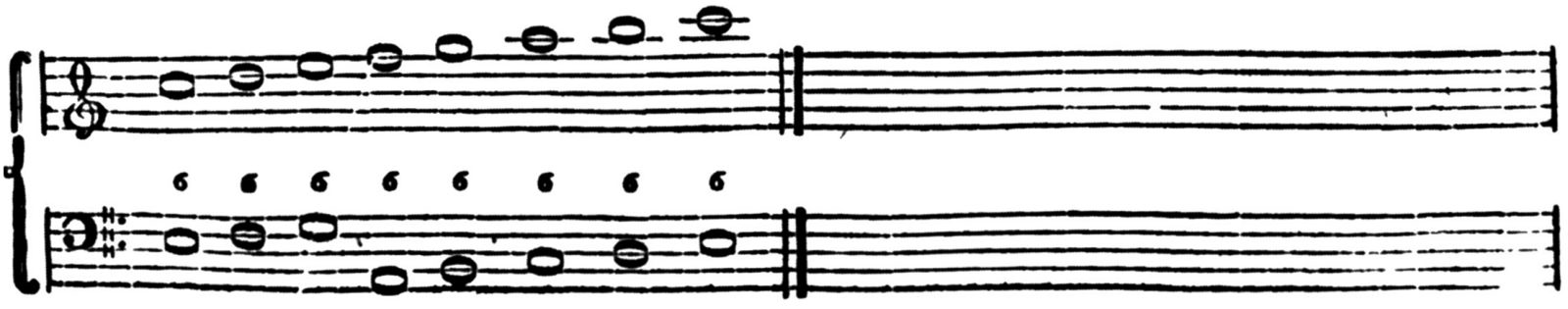

The Gesangleiter begins quite simply. Declaring C, F, and G Grundbaßnoten and the remaining pitches Nebenklänge or Mittelbaßnoten that arise from the triads above C, F, and G (Example 3), Riepel first demonstrates that this approach results in a complete scale (Example 4) and then goes on to harmonize this ascending scale in treble clef using only the Grundbaßnoten C, F, and G (Example 5).

Example 3: Gesangleiter §. 1, p. 6

Example 4: Gesangleiter §. 2, p. 6

Example 5: Ascending Gesangleiter §. 3, p. 7

While it seems implied that the pitches in the top voice are harmonized by the triad to which each pitch belongs, two pitches, G and C, which both are part of the triads on C and G and C and F respectively, are harmonized in the ascending scale with C without explanation.[17] Commenting on the resulting leaping root motion in the bass, Riepel suggests that if composers would use only Grundbaß- and no Mittelbaßnoten, compositions would seem desolate and barren. Thus he suggests that the root of the chords could be replaced with by its third, which “the old have called Nota median (mediating note).”[18]

Example 6: Ascending Gesangleiter §. 4, p. 7

Example 6 reproduces the harmonization of the ascending Gesangleiter, which, except for the final C, replaces the chordal roots with the thirds where possible. That is scale degree ➌, E, and ➏, A, which are the chordal thirds of the triads on C and F respectively, continue to be harmonized with their roots. However, scale degree ➐, B, is not harmonized by its root G, but D, which in this context is ‘mediating.’ Indeed, Riepel’s chordal harmonization of the ascending Gesangleiter §. 4 (Example 7), demonstrates that the scale degree ➐, B, is harmonized by its third, D. Riepel thus expands the repertoire of chords adding a B diminished chord. It is noteworthy that he does so without making an attempt to explain the origin of the diminished chord. Riepel, however, points out that even though scale degree ➊, C, is harmonized by scale degree ➂, its third E, in the bass, that this is meant as a continuation in the middle of a melody, “otherwise, there should not be the note E at the beginning but the Grundbaßnote C.”[19]

Example 7: Harmonization of the Ascending Gesangleiter §. 4, p. 8

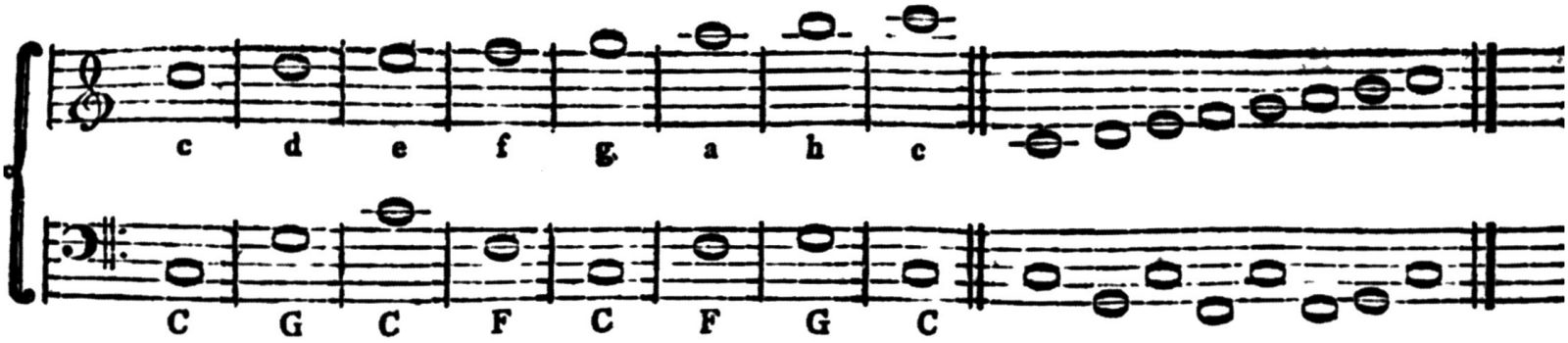

The next two harmonizations of the ascending Gesangleiter (Examples 8 and 9) use only consonant thirds and sixths. “I also imagine,” Riepel writes, “that, except at the beginning and the end, there can always be thirds between the melody and the bass, may they be mediating or not mediating, Mittelbaß- or Grundbaß-like, for example:”[20]

Example 8: Ascending Gesangleiter §. 5, p. 8

Example 9: Ascending Gesangleiter §. 6, p. 8

In addition to using thirds and sixths, Riepel suggests that scale degrees ➌, E, and ➏, A, could also be harmonized with fifths (Example 10) and octaves (Example 12) between the outer voices:

Example 10: Ascending Gesangleiter §. 7, p. 9

Example 11: Right Hand Chords for the Ascending Gesangleiter §. 7, p. 9

The fifth below E results in an A minor, the fifth below A in a D minor triad as shown in Example 11. In addition, since the D remains stationary in bass through the ascent from scale degree ➏–➐, the outer voices create a 5–6 motion. While the fifths below scale degrees ➌ and ➏ resulted in root position chords, Riepel harmonizes the octaves below ➌ and ➏ (Example 12) in two different as shown in Example 13:

Example 12: Ascending Gesangleiter §. 8, p. 9

Example 13: Two Harmonizations of the Ascending Gesangleiter §. 8, p. 9

The two harmonizations in Example 13 share the bass of Example 12; however, Riepel interprets E and A first as chordal roots resulting in E minor and A minor chords and then as the chordal thirds of the C major and F major chords respectively. Figure 7 schematizes the two different harmonizations of the octaves in comparison:

Figure 7: Two Harmonizations of Ascending Gesangleiter, §. 8

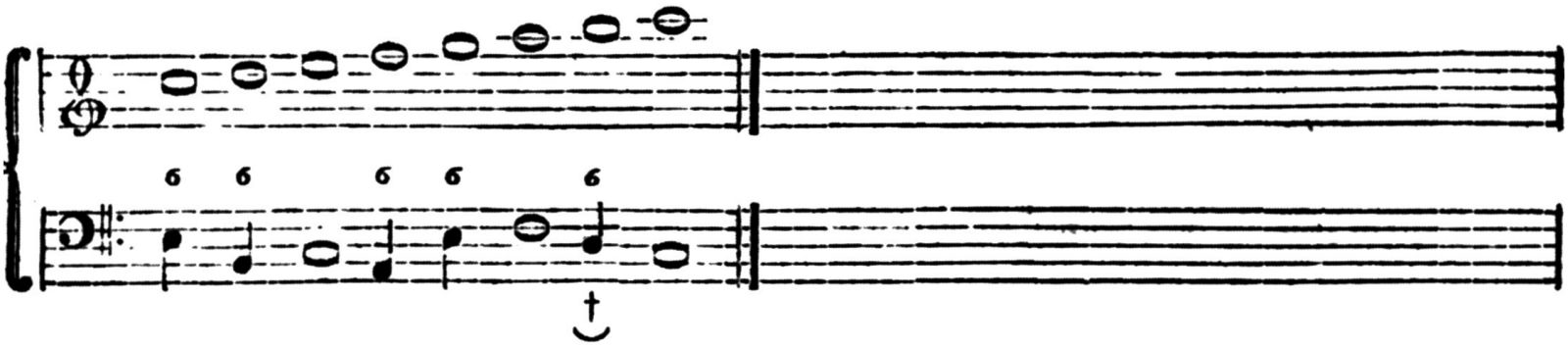

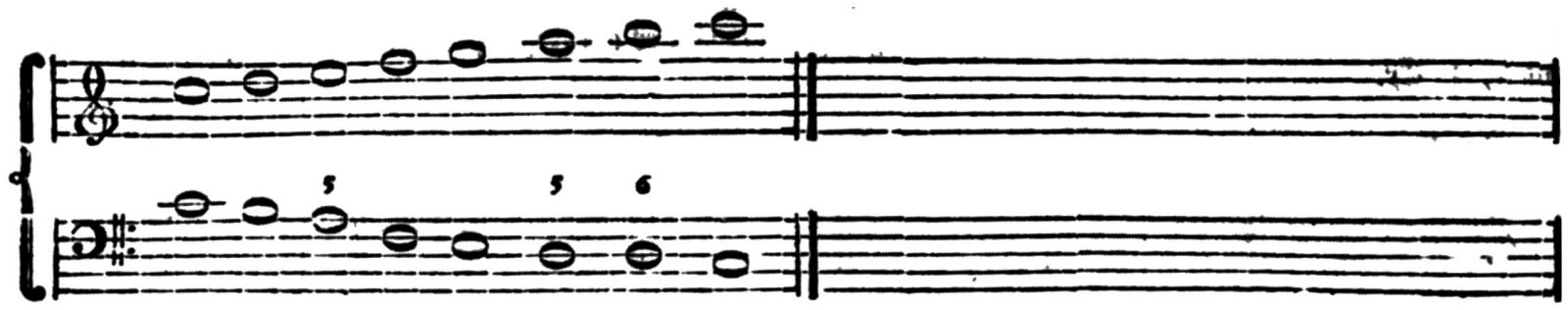

Ascending Gesangleiter §. 9–11 (Examples 14–17) introduces the use of the chordal seventh. Example 14 harmonizes scale degree ➍ in the soprano with ➄ in the bass, resulting in a minor seventh. In his brief discussion before the example, Riepel acknowledges that the minor seventh, while a dissonance, now constitutes a common sonority, especially in a chord containing also a third and fifth.

Example 14: Ascending Gesangleiter §. 9, p. 10

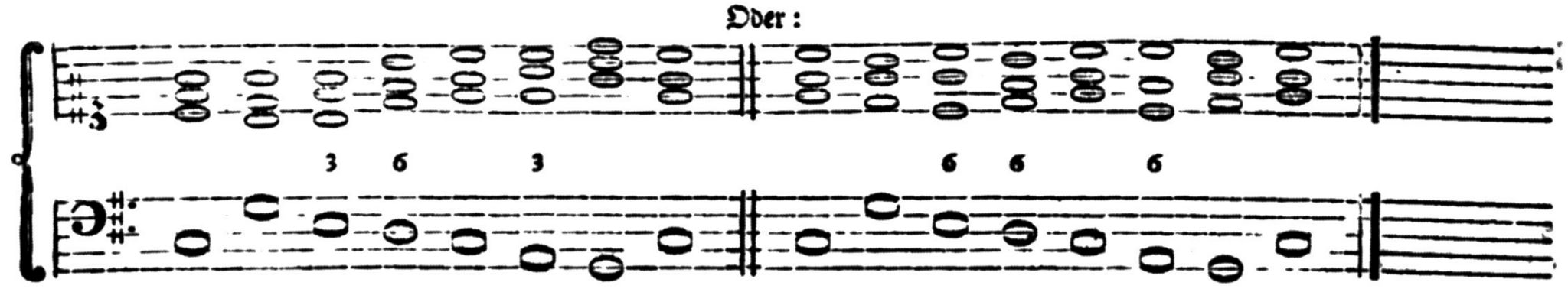

However, the unusual resolution of the chordal seventh, ➍ moving stepwise up to ➎, is far from ideal and Riepel presents six resolutions reproduced in Example 15.

Example 15: Ascending Gesangleiter §. 9, p. 10 – Resolution of Chordal Seventh

Discarding No. 1 and No. 4 because of the outer voices moving into a fifth, Riepel accepts No. 2 where ➍–➎ in the soprano is countered by ➄–➂ in bass; however, he prefers Nos. 3, 5, and 6 where the seventh resolves stepwise down. Examples 16 and 17 demonstrate how ➋ and ➍ and ➌ and ➐ can be harmonized with a 4/2:

Example 16: Ascending Gesangleiter §. 10, p. 10

Example 17: Ascending Gesangleiter §. 11, p. 10

Finally, Examples 18 and 19 demonstrate the inclusion of chromaticism:

Example 18: Ascending Gesangleiter §. 12, p. 10

Example 19: Ascending Gesangleiter Example §. 13, p. 11

Example 18 consists of two chromatic segments, each having three descending half steps: ➀–➆–♭➆–➅ and ➄–♯➃–➃–➂ ending on an F6 and C6 chord respectively. The chromatic ascent in Example 19 clearly moves towards scale degree ➅, but as the progression ends with the arrival of scale degree ➊, C, in the soprano, the harmonic orientation of the chromatic motion leaves a certain ambiguity, as it can be heard as both: ➃–♯➃–➄–♯➄–➅ or ♭➅–♮➅–♭➆–♮➆–➇.

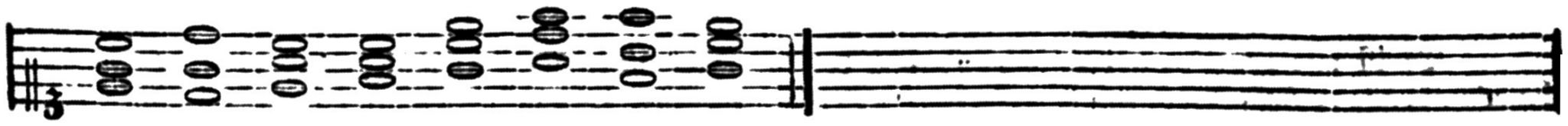

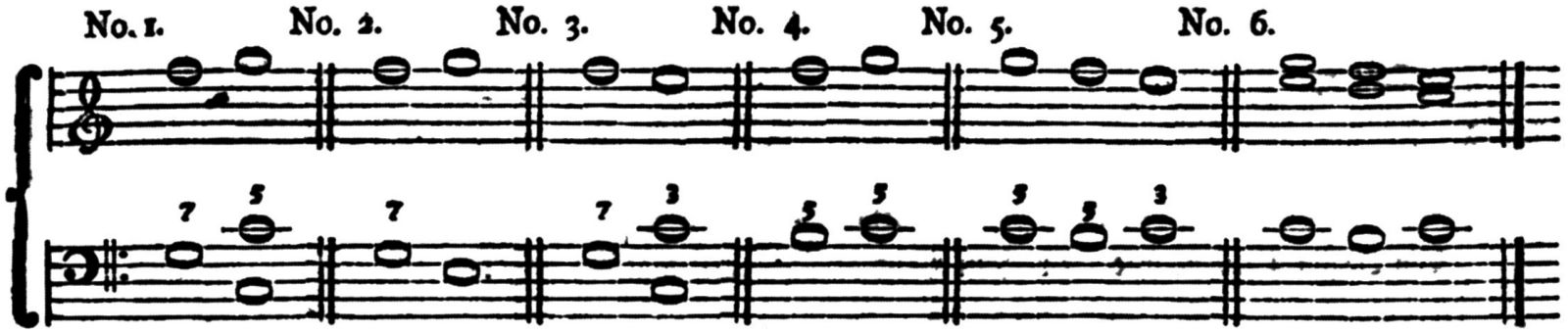

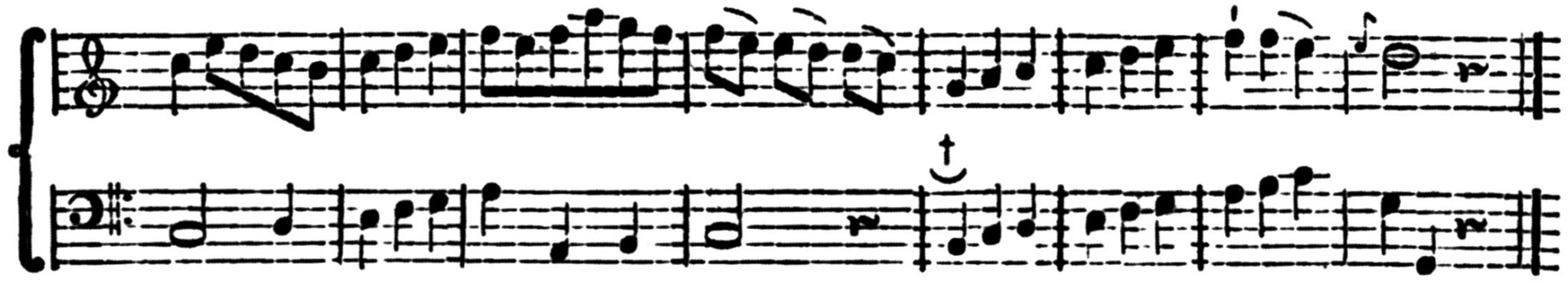

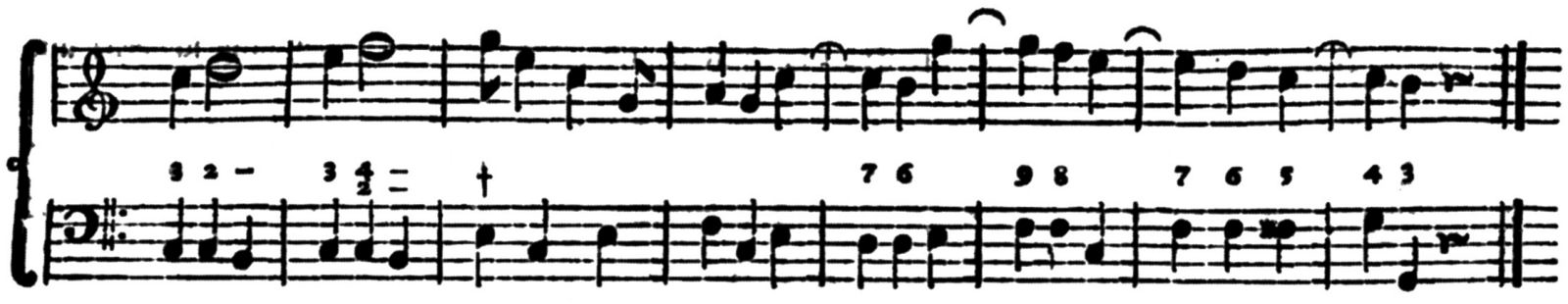

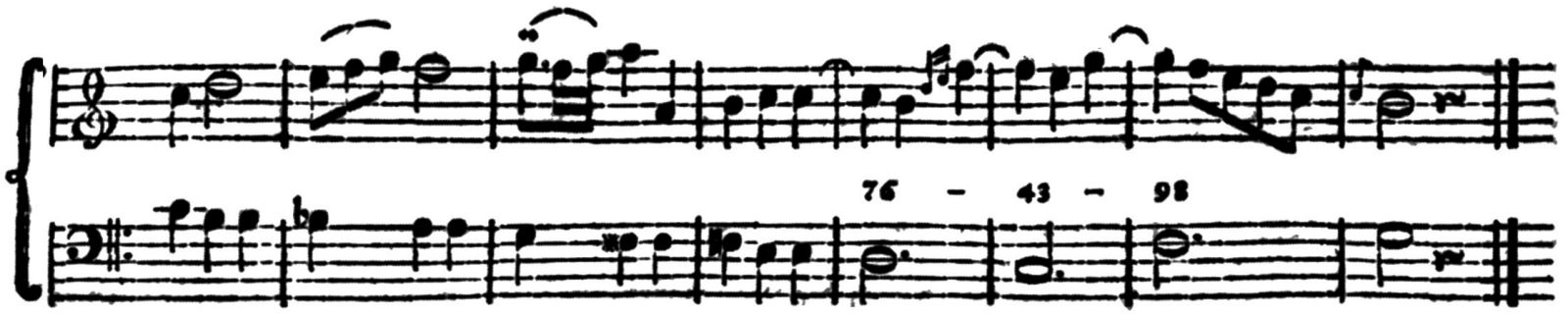

Examples 20–30 reproduce the examples with which Riepel demonstrates the application of the eleven rules (§. 3–13) for writing a bass below the ascending Gesangleiter in major. What is striking is that all eleven examples could serve as the first part of a minuet. Consisting of eight measures, which are divided into two four-measure phrases, the first phrase ends on the tonic, and the second on the dominant. While most examples end with a half cadence, two examples, Examples 20 and 26, modulate to the dominant and end with an authentic cadence in the key of the dominant.

Example 20: Application of the Ascending Gesangleiter according to §. 3, p. 11

Example 20 uses only root motion to harmonize the melody, mm. 5–8 modulate to G, which shifts the root motion from C, F, and G to G, C, and D.

Example 21: Application of the Ascending Gesangleiter according to §. 4, p. 12

Example 21 uses first inversion chords where possible, but includes also a cadential 6/4 chord at the half cadence in m. 8. That is, when chordal thirds appear in the melody, the bass always takes the root of the chord, as seen on the last beat in mm. 1 and 3 where E and A are harmonized with C and F respectively.

Example 22: Application of the Ascending Gesangleiter according to §. 5, p. 12

Example 22 contains two extended passages harmonized in parallel thirds (from the last beat of m. 1 to the downbeat of m. 3 and last beat of m. 5 to the last beat of m. 7).

Example 23: Application of the Ascending Gesangleiter according to §. 6, p. 12

Example 23 contains two extensive passages in parallel sixths (last beat of m. 1 – last beat of m. 3 and last beat of m. 5 – last beat of m. 7). However, Riepel notes that the bass starting at † seems more like an inner voice and he rewrites mm. 5–6 by placing the bass as the melody harmonized in parallel 3rds.

Example 24: Application of the Ascending Gesangleiter according to §. 7, p. 13

Example 24 presents the 5ths below ➌ and ➏, resulting in the Am (m. 2 beat 1) and Dm (m. 5 beat 1). Interestingly, Riepel comments how the passage at (O), in mm. 4–5, while acceptable, sounds better when fully voiced. However, Riepel’s harmonizations concern only the motion from ➃–➂ in the bass, harmonizing them with first inversion chords d6–C6 respectively, which contradicts the B in the melody.

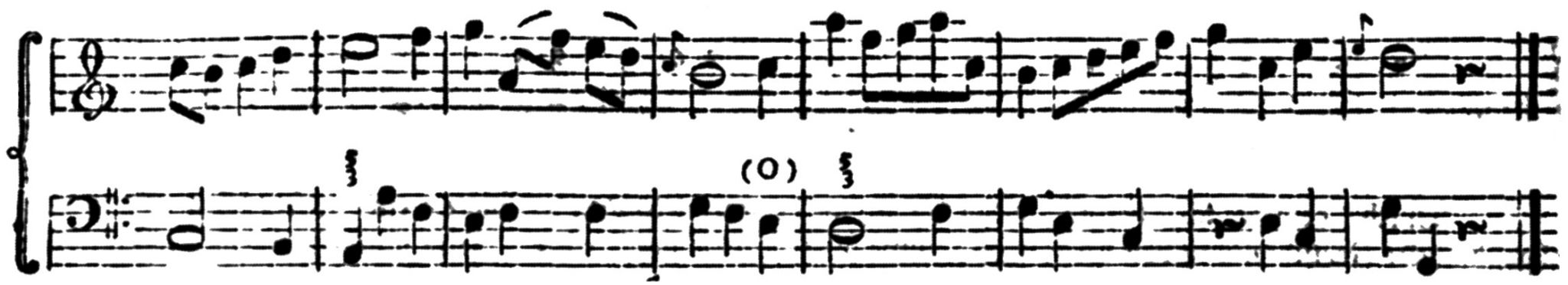

Example 25: Application of the Ascending Gesangleiter according to §. 8, p. 13

Example 25 contains the 8ves below ➌ and ➏, resulting in Em and Am chords on the downbeats of mm. 2 and 3 respectively.

Example 26: Application of the Ascending Gesangleiter according to §. 9, pp. 13–14

Example 26 includes chordal sevenths. Unlike §. 9 which only focused on the resolution of the minor seventh in the context of the dominant, (Q) presents a half-diminished seventh chord above ➆, while (P) and (R) treat the V7 in root position and inversions.

Example 27: Application of the Ascending Gesangleiter according to §. 10, p. 14

Example 27 includes 4/2 below ➋ and ➍ (ii4/2), both using the repeated note paradigm (➀–➀–➆–➀), harmonized with 5/3–4/2–6/3–5/3. However, at †, the bass moves not to ➀, but using ➂–➀ in order to avoid moving into the fifth C-G (downbeat of m. 3) in the outer voices.

Example 28: Application of the Ascending Gesangleiter according to §. 11, p. 14

Example 28 features 4/2 below ➌ and ➐. However instead a V4/2of IV, ➌ is harmonized with a V4/2of ii with ➄ in the bass, resolving to a d6 on the downbeat of m. 4.

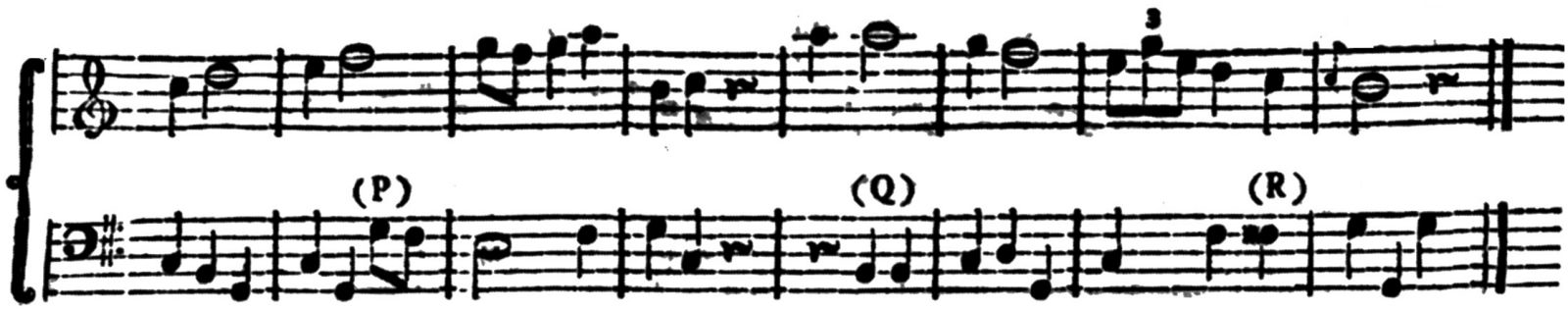

Example 29: Application of the Ascending Gesangleiter according to §. 12, p. 15

Example 29 contains the two chromatically descending bass segments (➀–➆–♭➆–➅ and ➄–♯➃–➃–➂) ending on an F6 and C6 respectively.

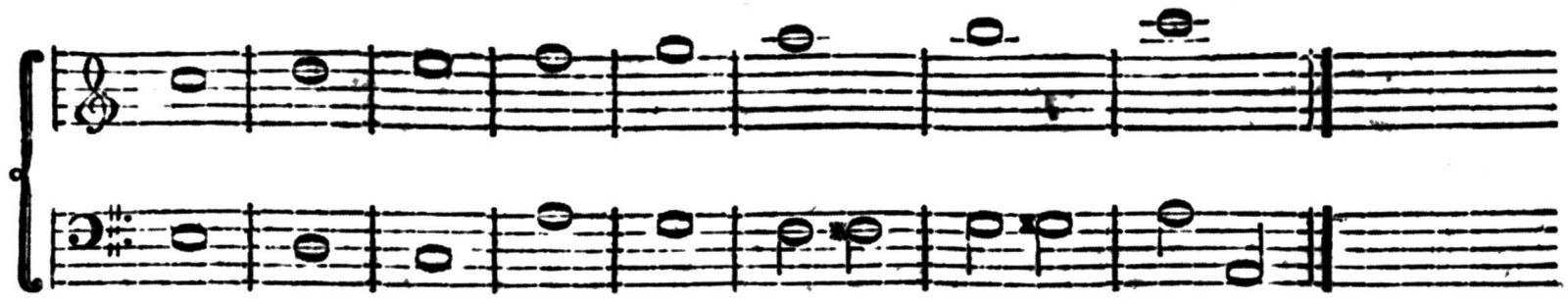

Example 30: Application of the Ascending Gesangleiter according to §. 13, pp. 16–17

Example 30 contains a chromatically ascending bass segment. Unlike §. 13, where its harmonic interpretation was ambiguous because the segment ended the example, Example 30 clearly remains in the key of C because of the phrase ending on the dominant.

Notes

See Wolf 1981, 132. | |

See for example the review in Marpurg 1775, 342-343. | |

See Emmerig 1984 for a full listing of Riepel’s oeuvre and Emmerig 1996 for an edition of Riepel’s complete theoretical writings including a transcription of the chapters that only survived in manuscript form. | |

See Eckert 2000 pp. 14–54 and Eckert 2007 pp. 95–96 for a detailed discussion of the dialogue structure and its significance to Riepel’s theories. | |

See British Library (Anton Bachschmidt) [Add. 31034] fol. 71a-92b. | |

“An den Baßschlüssel schließen sich in dem Exemplar in GB-Lbl. 22 Blätter (fol. 71a – 92b), and ‘which do not appear in the published edition’ (Hughes-Hughes III, 326). Bei diesen Blättern handelt es sich zweifelsfrei um Bruchstücke früherer Manuskriptfassungen u. a. des Baßschlüssel – in der ursprünglichen Dialogform! – und des Harmonisches Sylbenmaß III; einige Teile konnten noch nicht identifiziert warden. Anfangen darüber, ob es sich um autographe Blätter oder Kopien handelt, sind nicht möglich, da gesicherte Autographen aus früheren Jahren Riepels zum Vergleich fehlen. Literatur: Mettenleiter, 52 – Twittenhoff, 38 ƒ. and 107 ƒƒ” (Emmerig 1984, 167–168). | |

Emmerig 1996, 852–853. | |

See Emmerig 1996, 578–585 (Sechstes Capitel vom Contrapunct. Joseph Riepel, Sämtliche Schriften zur Musiktheorie. Vol. I. Wien: Böhlau Verlag, 527-634). | |

See Christensen 1992 and Jans 2007 for an extensive discussion and historical context of the octave rule. | |

Following Gjerdingen 2007, I will identify the scale degree of notes in the bass using ➀, ➁, ➂, etc. based on the major scale. That is, regardless of mode, ➆ will always identify the leading tone, the major seventh above the tonic. I use accidentals to identify any alterations or to clarify ambiguous moments; for example, ♭➆–♮➆–➀ identifies a motion from the minor to the major seventh to the tonic. Similarly, I use ➊, ➋, ➌, etc. to identify scale degrees of notes in the soprano. | |

See Emmerig 1996, pp. 578–586. Wiener 2003 has pointed out Riepel’s harmonic revisions of counterpoint example by Fux. | |

“Ein vollkommener Accord besteht, wie bekannt, in der Terz und Quinte, es mag die Terz gleich über oder unter der Quinte zu stehen kommen.” And a footnote explains further, “In der Praktik gilt ein Accord oft für vollkommen, wenn anstatt der Terz auch nur die Quinte und Oktave, oder anstatt der Quinte nur die Terz und Oktave zu hören stehen etc” (Riepel, Baßschlüssel, 1). | |

“Da denn der Quartsprung f und der Quintsprung g von Natur vollkommene Accorde verlangen, und aber bey deren unmittelbaren Fortschreitung leicht verbotene Quinten oder Octaven sich ereignen, so haben schon die ältesten Meister zur Vermittelung eine gute Nothhülfe, nehmlich den Sextquintenaccord erfunden; und ob er gleich ein wenig stumpfsinnig lautet, so wird er doch nicht minder zum Septimen- als [auch] Quartsprung gern gebraucht. Z. Ex. <Example>” (Riepel, Baßschlüssel, 1). | |

Lester 1992, 270. | |

“Ich war eben so begierig, diesen Tractat zu lesen, als ich begierig war zu wissen, auf was Art Nicolaus Klim mitten in der Erde endlich noch eine fünfte Monarchie angetroffen habe” (Riepel 1755, 53 fn). | |

“Zu voraus muß ich anmerken, daß der uralte Baß zum Gesange von Einigen (vielleicht erst in diesem Jahrhundert) für systematisch erklärt worden ist. Dieser Erklärung zufolge hat die ganze Otavleiter nur drey Grundbaßnoten, die übrigen sind Neben- oder Ausfülltöne, die ich aber aus Achtung für ihre guten Dienste wenigstens Mittelbaßnoten nenne” (Riepel, Baßschlüssel, 6). | |

Since C appears only at the beginning and the end of the scale, it makes sense to harmonize it with C, and a possible reason for not harmonizing G with G would be that since G is preceded by F, which is harmonized by F, harmonizing G with a G would create parallel octaves. | |

“…von den alten Nota medians (vermittelnde Note” genannt” (Riepel, Baßschlüssel, 7). | |

“[…], sonst müßte es (wie bekannt) zum Anfange nicht di Note e, sondern die Grundbaßnote C seyn” (Riepel, Baßschlüssel, 7). | |

“Auch stelle ich mir vor, daß Terzen außer Anfang und Ende zwischen Gesang und Baß durchaus statt finden, sie seyen zum Gebrauche meinethalben vermittelnd oder unvermittelnd, mittelbaß- oder grundbaßmäßig, z. Ex.” (Riepel, Baßschlüssel, 8). |

Dieser Text erscheint im Open Access und ist lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz.

This is an open access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.